The End of Spaghetti For Brains

Ten years ago, at the age of thirty-six, I started university as a mature student. Much like high school, from which I dropped out, I quickly got in trouble.

The university had one of the highest paid vice chancellors in the country. Her salary was near double that of the Prime Minister. This despite the fact that it was one of the smallest universities in the country, in the bottom half in terms of rankings, with no special claim to institutional leadership. It was, however, a very good place to study art and criticism, and to find yourself in the company of fellow weirdos. That is to say, it was ripe for gentrification. The vice chancellor was the living embodiment of that gentrification.

I wrote a poem about her. I took the piss out of her for earning so much money while doing so little for the institution of higher learning, to say nothing of the town the university occupied. I compared the forces that landed her in the top job to those of the psychotic pigs Jesus chased off a cliff. I asked her why gentle Jesus chased the pigs off the cliff. I created a collage with her official portrait and the letters “F” and “U” over her eyes, the initials of the university, then used this for a cover. I printed 50 copies of the poem and handed them out to people I thought would find them funny, including my woefully underpaid and overworked tutors. My tutors loved it. Then I got an email from the uni’s head of communications, requesting in sombre tones to meet and discuss a particular, albeit unnamed, matter.

Mr Comms had thinning hair; he was gangly and paunchy at the same time; he wore an ill-fitting suit and pointy shoes, both common to the 2010s. Mr Comms used to work in British media and it showed in his demeanour as well as his clothes. He may be heading those sorts of well-remunerating communications befitting the genocidal class as we speak; I wouldn’t doubt it. We met in the canteen and he pulled a copy of my poem out of the inside pocket of his ill-fitting blazer. He slid it across the table to me like contraband, speaking sotto voce:

Have you seen this?

Yes, I wrote it.

You wrote this? And you’re admitting it?

Yes.

This is hate mail.

Please tell me what you find objectionable in the poem.

What, you want me to go through it line by line?

I’m a student of literature. That’s what we do.

He asked me about the pigs. I explained. He threatened me with expulsion on the grounds of “gross misconduct”.

Now, I’ve spent enough time banging heads with figures of authority to know when it’s worth it and when it isn’t. But I have a fatal intolerance for taking editorial notes from mercenary hacks in ill-fitting suits. My wife once (half-)joked that you could tell how a person fucks by the way they dress. I wasn’t about to get fucked by a normie in winklepickers.

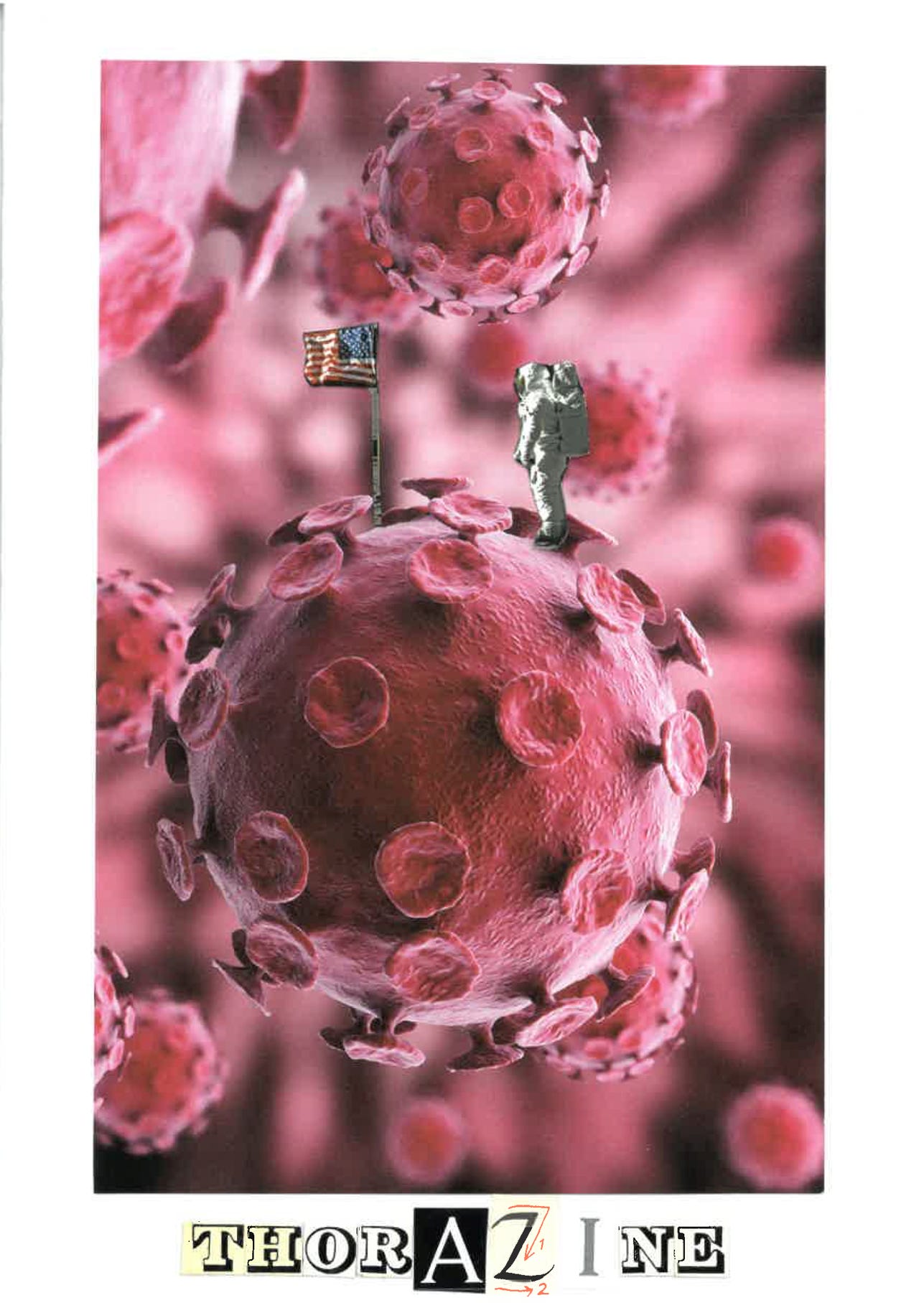

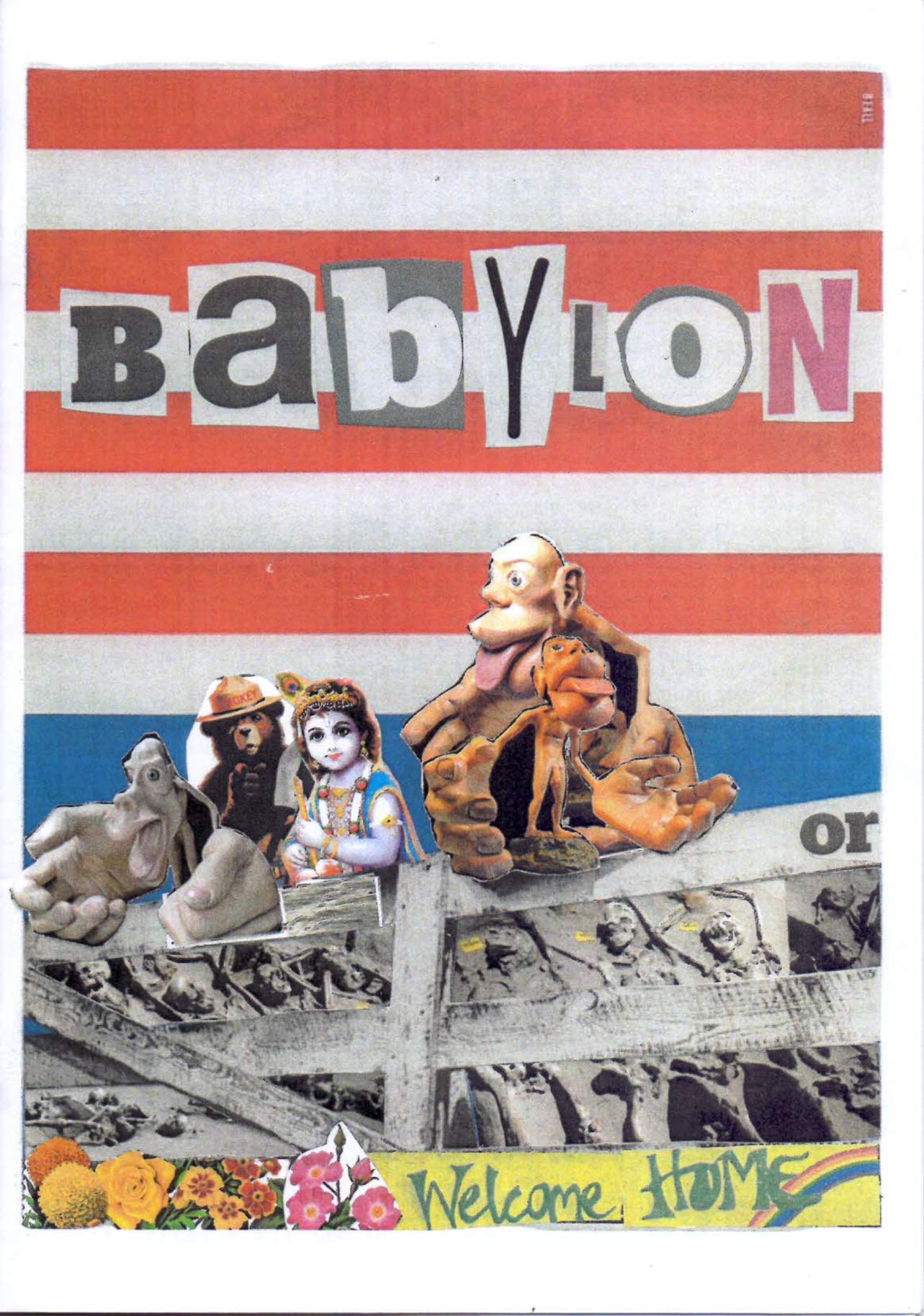

And that is how Spaghetti For Brains came into being: a pamphlet press, cheap A5 pamphlets printed and stapled, the text carefully typewritten and photocopied by yours truly, the collage done with discarded ephemera and a Pritt stick.

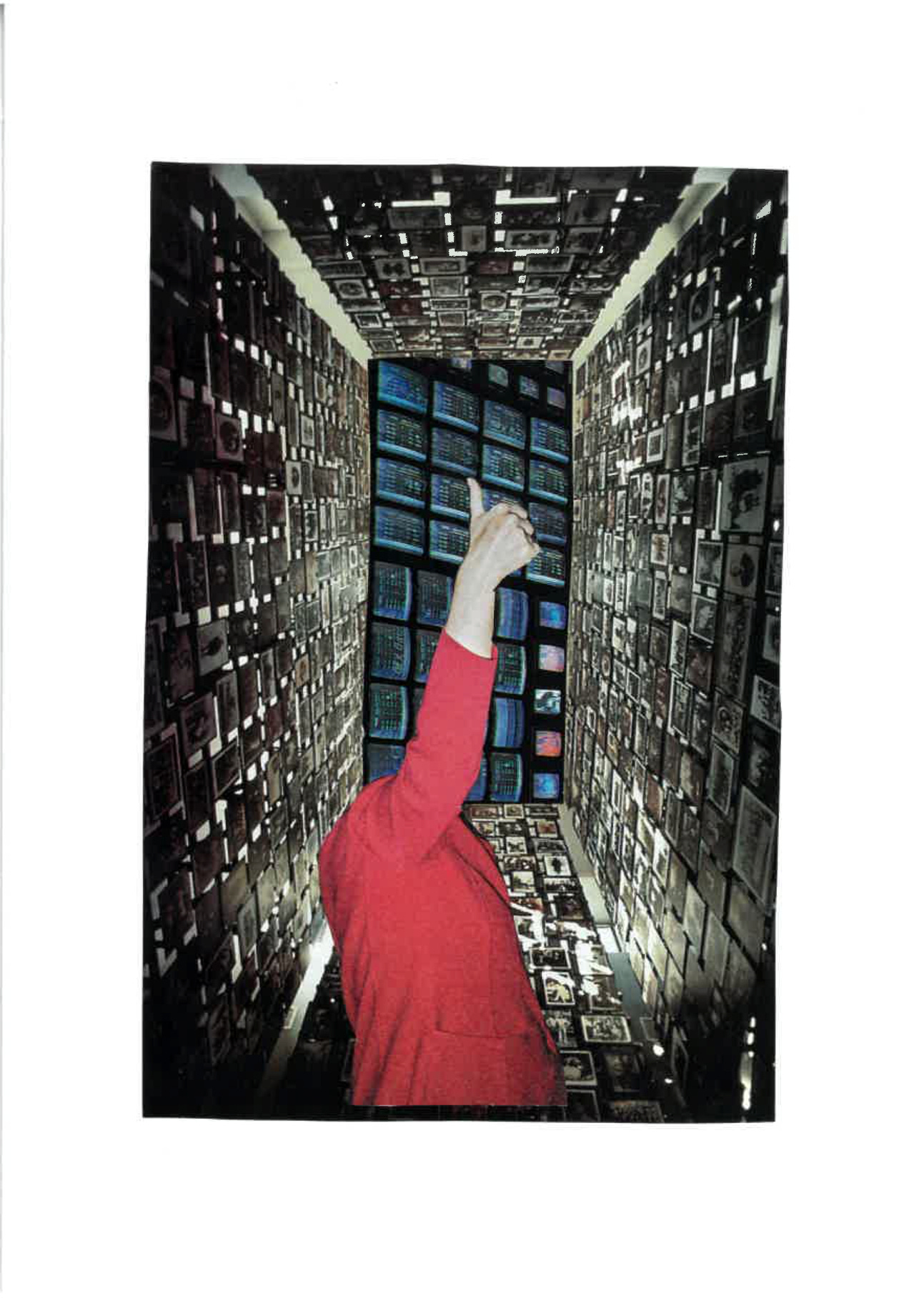

The last SFB pamphlet came out in 2020, just as lockdown was announced. It wouldn’t be possible to sell copies for the foreseeable future, so I thought I would start a podcast and simply read the writing aloud. At the same time, the campaign to nominate Bernie Sanders as the Democratic candidate for President was just beginning. People here in Glasgow kept asking me about it—and there was a lot to tell. So I started the Spaghetti For Brains newsletter, this newsletter.

My old friend Norm joined me on the podcast. He was active in the Bernie campaign and we talked shit, told jokes and wondered/disagreed/cackled aloud about politics. We kept it up weekly (mostly) until my life was suddenly pulled apart in a vortex of eviction, depression, pregnancy and death. The podcast fizzled out. Norm and I still have ideas for episodes and sometimes we can find the time to record. Maybe one day we’ll do some more.

In the intervening half decade, I’ve changed as the world has—not always for the better, neither the world nor myself. No one, I think, can claim to have kept pace. If you widen the scope to include “the left”, I would argue that even fewer of us have. Ethno-nationalism, fascism, craven liberal democracy, democracy of form with no content—ghosts of the nineteenth century disguised as ghosts of the twentieth—haunt us with renewed menace, with the vigour of the undead, on a trajectory from nowhere left to go perhaps as far as the end of the world. The menace is real. Some ghosts really can hurt you. Without a vision of freedom to animate the opposition, and the bedraggled filaments of civil society to embody that vision, we find ourselves prone before the oncoming train, tied to the tracks, an old cartoon, a tired meme. Some on the left seriously contend that there is hope in the unserious possibility of the track running out before we’re run over; that the train will derail, crash, disintegrate, disappear. Then, somehow, we’ll find ourselves unbound and upright, ready to—what? Rebuild the train in our own image? Lay new tracks to somewhere else? What?

And yet…

I refuse to despair. And I’ve never been surer of my commitment to our self-emancipation from the delirium of class society. There’s simply too much at stake to wallow in cynicism. And there’s no cynicism like the satiating despair of a person who once subsisted on an abundance of hope.

That said, even the name “Spaghetti For Brains” is characteristic of an irony born of that despair so redolent of the previous decade. I’m not feeling ironic anymore—not in the scant minutes I get to myself, sitting down to write; not in the wee hours spent staring into the distant gloaming horizon of further vortices pulling my life apart; not when my fate collides with yours because we happen to occupy opposing currents in the tornado; nor when we’re so outpaced and outflanked by our enemies that they become practically invisible, despite sucking up all the representational oxygen in the room.

Down here in my mousehole, writing is fighting. And I think I should be fighting in my own name.

So I’m retiring the Spaghetti For Brains imprint. What this means in practice is that this newsletter will still appear in your inbox at the irregular and embarrassingly infrequent rate that it always has, but it will bear my name, as will the website. (My name is Ben Kritikos, by the way.) I’ll still be writing about music, the social history of records, recording, workers in music producing music as a commodity—a story whose central character is not any particular style or individual musician, but the US empire itself. It’s the story of what an American is (or a Scot or a Brit) and the ever-contentious question of who gets to decide. The only change will be the byline.