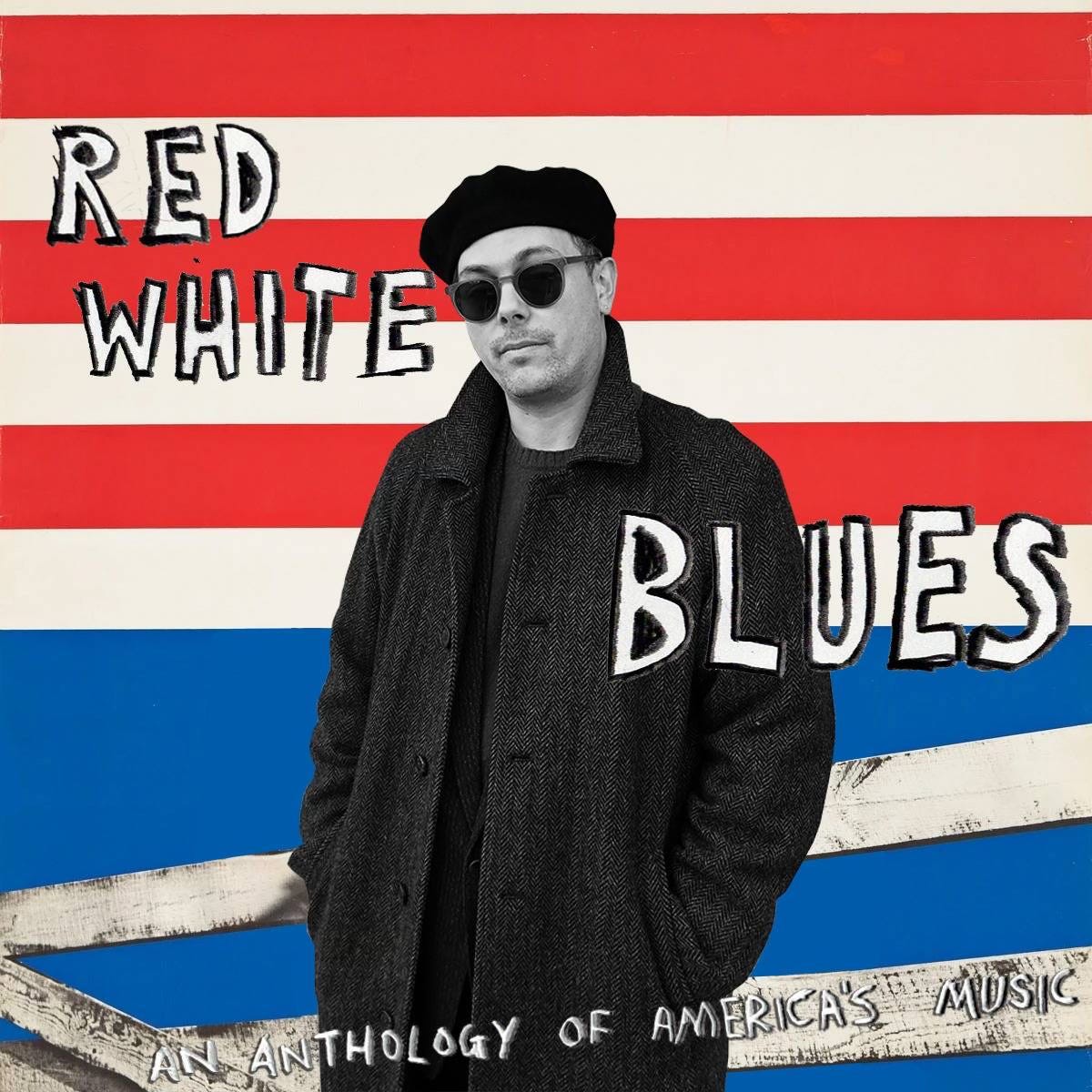

"Seeing the World in a Piece of Plastic"

A Guide to Red White Blues Episodes 1-21

Since April of 2023, I’ve been hosting a radio show on my local community radio station. The show is called Red White Blues and it’s about jazz records, petroleum and the making of America.

The idea for the show is that by telling the story of jazz records as objects, tracing the development of both jazz music and also the infrastructure of American consumerism, you could tell the story of how the United States came to a position of global dominance. This is in no small part because the two things—jazz and consumerism—developed at the same time.

Our reliance on petroleum, in the form of fuel oil and plastic specifically, transformed the world and transformed us. We are all the product of a concrete world of automobility and the oil-fuelled mechanised production of plastic consumer goods. Our ideas about citizenship, about nationhood, about culture and counterculture, about the past, the present and the future all arise from a material reality constructed almost entirely from oil.

Vinyl records were among the first of these plastic consumer goods, and jazz was, at the time that records went from being made of shellac to being made of oil-based plastic, America’s popular music. Before this, jazz had been an African American vernacular music, a kind of folk music; and after jazz’s stint in the mainstream, it became an art music with modernist ambitions. The lineage of jazz moving from a folk music to a popular music to an art music moves in parallel to the lineage of the modern American consumer-citizen coming into being. In this way, we can “see the world in a piece of plastic”, to use the words of Kyle Devine.

American capitalism in the twentieth century promised prosperity. Now, in the twenty-first, we’re choking on microplastics, endangering our own species as well as most others through anthropogenic climate change, and living through an endless series of socioeconomic crises without a sufficient explanation from the people who claim to be experts on the subject. Our culture does little to comfort or educate us, let alone to foster solidarity. Our technology creates as many problems as it solves. Our work, if we’re “lucky” enough to have it, is frequently gruelling, mostly boring and oftentimes meaningless—we work longer and harder for lower wages and fewer benefits. Even people from comfortable backgrounds struggle to feed, clothe and house themselves or even to remain in once place, while everyone else faces the prospect of adding to the record spike in deaths of despair. Instead of getting easier, life gets harder, more lonely, more angry—and more difficult to change.

The “American way of life”, now spread across multiple parts of the globe at the expense of almost all the others, has sold itself as freedom; yet here we are, discovering that this kind of “freedom” equals murder, misery, ecological catastrophe and a powerlessness to do anything about it.

Jazz is often described as “the only true American art form” and I think that this is true—in a sense. The story of these jazz records, the cultural and infrastructural landscape that enabled them to come into being and the extremely talented people who laboured to keep the music alive, also offers (in my opinion) a vision of real freedom, imagined by many of the people who were blocked from taking part in the American way of life. It’s easy to scoff at the very idea of “American culture” when you’re intoning it to people whose own culture is comprised of the Simpsons and McDonalds, where “America” is not so much a place as a brand concept. But jazz represented, at its best, both a resistance to this debased form of American civic identity and also, as an activity bound up with both commerce and culture, a key to understanding how that normative American consumer-citizen came into being.

I’m not saying that jazz records hold any answers to the problems we’re facing, but looking at how the records were made, the physical world that gave rise to them and the societies that inhabited it, we can trace the path that got us here, to better understand it—and, crucially, to change it.

Below is a list of all the scripted episodes to date, in reverse chronological order, with a link to SoundCloud and a short description. For a full list of episodes including track listings, you can visit our Instagram.

Episode 21: An open letter to my son, for Christmas.

Episode 20: “A Plastic Shadow”: V-Discs, Vinyl and the Second World War

[taken from the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/V-discs1-991943-1944]

On this episode, we look at the history of V-Discs and the rise of vinyl.

In August of 1942, the American Federation of Musicians declared a strike: an all-out ban on members going into the studio and recording music. The strike was called to force the big three record companies to increase the royalty rate on recorded music paid to musicians, which had become a substantial part of music workers’ business in an American culture structured around the production of consumer goods. The strike would last for two years, in which time no commercial records were made.

But the US military and the big labels joined forces to create V-Discs (or Victory Discs)—non-commercial records for the enjoyment of the American soldiers and staff stationed abroad. Records up to this point were made of a rationed material sorely needed in the production of armaments: shellac. With the US having an abundance of oil, the petroleum-based vinyl record came to prominence and it’s been that way ever since.

Oil-based plastic didn’t just shape music manufacture in its own image, though—it shaped American consumerism, which undergirds the world as we know it through mass production and mass communication, the end result of which is masses. It’s us.Episode 14: Bebop, the Nuclear Age and the American Century

In this episode, we explore the creation of an American “mainstream”, forged by empire-minded plutocrats like Henry Luce (of TIME, LIFE and Fortune magazines) in the fire of nuclear energy, with sound collage capturing the ways that military and civil technology was presented to the public as the conquest of the American way of life over other countries and even nature itself. We listen to records featuring leading modernists in their first roles as sidemen, wartime bootleg recordings and V-Discs—the only records being made during a two-year strike that brought the record industry to its knees between 1941-1942—as well as the earliest Bebop records that seemed to appear, in revolutionary fashion, fully formed from nowhere in the mid-1940s. We close out with a track that captures the counterrevolutionary current to Bebop.

Episode 10: Black, Brown and Beige

On this episode we listen to Duke Ellington’s sprawling jazz suite Black, Brown and Beige, recorded only once in its entirety and never played in full after 1943 when this record was made. Ellington uses this “tone parallel” to tell the story of Black Americans becoming Americans, but listening to this record 81 years on, it throws up all kinds of questions about the United States itself—about the nation, “the people”, and who a place belongs to, and why.

Episode 8: Magnetic Tape and the Citizen as Consumer

On this episode, we interview the sound archivist and host of @radio_buena_vida’s Member Ship Card Conor Walker. Conor brings us through the history of magnetic tape and its impact on both sound recording, the record industry as well as music listening habits that helped shape the American citizen-as-consumer.

On this two-part episode, we hear records from the 1930s that paved the way for what we now call 'the Swing Era’. These records set themes that American culture would be forced to struggle with by the end of the decade, and that would come to define the era: issues like race, class and the tension between art and popular culture.

And this era, the Swing Era, was a product of oil, a product of the car, the highway, the suburbs and the teenagers who lived there. From the mid-thirties until the end of the war, it would become what Gunther Schuller describes as ‘that remarkable period in American musical history when jazz was synonymous with America’s popular music’. It would also be the only time that this was true. The age of oil would eat its own children.

Episode 4: The Passive Voice

On this episode, we hear Charles Mingus’s 1963 masterpiece The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, and Ben reads The Passive Voice: notes from 2020 reflecting on the George Floyd uprising.

Episode 3: Jazz: The Original “World Music”

Jazz is a uniquely American music, but like the United States and its patchwork of different nationalities, jazz is the product of a number of influences from outside of the United States. This also lent itself to influence the music of other countries. In this episode, we explore the ways that jazz used, and was used by, the music of cultures outside the United States, as well as how jazz represented a kind of “open source” radical cultural expression at home and abroad.

Episode 2: New Orleans and the Birth of Jazz

New Orleans is considered the birthplace of jazz, but where did jazz’s origin myth as “America’s Music” come from and what can it tell us about the United States’ ideas about itself?

Episode 1: “America’s Music”: an Introduction

We kick off the show and introduce the themes we’ll be exploring, as well as spinning some records just for fun.