Daddy Issues

An open letter to my son

This is the script from December’s episode of Red White Blues: an Anthology of America’s Music, which you can listen to here.

Dear Sal,

Merry Christmas, my lovely boy. I love you very much. For Christmas this year, I got you a present that you won’t even know exists for a long time. It’s this little letter and a few songs thrown in. I’m hoping that it ages well, that it takes on something it doesn’t have right now but should have by the time you can read it. It’s a gamble, but gifts are like that. You never really know how it will land.

Well, I also got you a balance bike, which I know you’re going to love.

That song we just heard was Thelonious Monk’s quartet playing his rendition of the children’s song “That Old Man” (or “This Old Man”, as I grew up calling it). Back in October, I dedicated a whole show to Monk’s music in honour of his birthday. I mentioned then that he was, as well as being a revered jazz modernist, the father of two children. Thelonious Monk’s reputation in the press was that of a kooky, mysterious, sometimes impenetrable personality—he was both valorised and denigrated with this exotic portrayal. But not many consumers of the media portrayal knew or cared that he was a father who, unusually for the time, did most of the day-to-day parenting while his wife worked.

There’s a lot you can say about this: about race, about mid-twentieth century gender politics, about jazz musicians and the way they were depicted in the media; but I think that, being a dad myself, I can safely say that people don’t expect much from fathers and the subject of fatherhood is often one that only comes up when you’re talking about someone making a hash of it—or not doing it at all.

This is, in part, the fault of dads themselves: many... make a hash of it or don’t do it at all. But many others simply won’t talk about their experience of fatherhood, as though the subject isn’t interesting or is somehow self-explanatory. I don’t believe either of these things about being father. In fact, I have an awful lot to say about it because I disagree with so much of what I have heard said about it and I really want you to know how much I’ve learned from being your dada.

At the time that I started writing this, you were nineteen months old. (You’re now two and a bit.) We’re raising you, your mother and I, with basically no help: no childcare, no family nearby, precarious housing and employment, and a civil infrastructure that reminds us daily that children, as well as people with disabilities and elderly people, are simply not important. Some people take the opposite view, as though raising children was magical and the only activity an adult needs in their life (maybe the sleep deprivation has addled their brains) and that a parent’s job is to shield their child from pain or struggle of any kind. Both extremes, it seems to me, don’t consider the fact that, though they might be small and not have full command of language yet, children are people.

The most striking thing about you, of course, is your loving personality. You’re so caring and accepting, so affectionate, so hungry for touch and play. You also need to know things—you want to know what’s happening when we sit on the toilet, where the pee goes, what’s inside our belly buttons (I really hate that you need to know this), what it feels like to touch the inside of our mouths, what my knees taste like. So in this time out of time, it’s reasonable to assume that, at the point this letter reaches you, you’ll want to know some other things that I might not be around to show or tell you. I hope that I am—for Christ’s sake, the idea that I won’t be there is torture to me—but just in case, I’m putting this down for you. Because I know what it’s like when a father isn’t there to share a certain kind of information that you might find useful, maybe even necessary.

To begin with, you’re half American. You’ll obviously already know this in an ordinary sort of way, but I want you to know what that actually means. On my radio show, we listen to jazz records because I think that jazz captures, better than any other music, the process of people in the United States becoming Americans: how the idea of who an American is expanded to include people who a short time before did not get included and how this expansion took a huge amount of fighting and resisting and refusing to accept the boundary of “American” and “not American”. I hope that I’ve been able to show that this process is not necessarily the conscious or deliberate result of concerted action by specific individuals, but something that happens across a shifting population, who are themselves intertwined with huge social and economic forces impossible to see when you’re standing in them. These lines between belonging and not belonging, of being from somewhere and not being from somewhere, are often arbitrary or horribly exclusive, even violent—the state or someone wielding power might have one idea, while the actual people who make up the population intuitively understand something else entirely.

You and I are a great example. I’m American—emotionally, culturally, legally—I hold an American passport and it’s where I was born and raised. But I haven’t lived there for decades. So the law says that you, my son who was born here in Glasgow, are not American. I haven’t even been able to get you a passport because I would have had to have lived in the US for two of the last five years, which I haven’t. But frankly—fuck that. Your dad is American, your grandparents are American, your great-grandparents—you might not have a passport, and you might not speak with an American accent, but you’re half American. Your name is Salvatore, for God’s sake. When I watch baseball on the tv, you shout “GO YANKEES”. The US State Department can kiss my ass.

But you’re also Scottish—you’re very much from Govanhill, despite not having a drop of Scottish blood. Your entire life consists of walking a circuit from the Community Gardens, Queens Park and the Hidden Gardens. You come to Nan’s and queue with me while I’m waiting for a roll. Sgt. Bob knows you. So do the very nice people from Women on Wheels who run the balance bike sessions. You’ve spent hours watching and chatting with the guys operating the diggers, cranes and the steamroller laying new payment on Queens Drive. You know what asphalt is because of them. You go to Locavore and steal clementines. When we’re in the playground at Govanhill Park, the other children playing next to you, who don’t all speak the same language as each other let alone as you, play with you like you’re one of them. Because you are.

Some people would disagree, but I would disagree with them. We live here—proof positive. Some people would say that belonging is about working hard or contributing something economically, some nonsense like that. The jelly-blooded evangelists of “tolerance”, the political dinner ladies stirring the melting pot. But Govanhill is great because the people who live here are not an amorphous mass of integrated suburbanites sharing a single civic identity that looks like an advertisement for an app. We’re all here doing our own thing, in between scratching out a living, wresting a bellyful from those who so munificently tolerate us.

Govanhill isn’t unique in this respect, nor are you. People have always moved to places and made them theirs, as they themselves came to belong to the place. But the hardscrabble existence of economic migrants goes one of two ways, in my experience: they come to the US or to Scotland (or wherever) and raise their kids as Americans or Scots, or they keep their kids close in a community of other people from the same country. Either way, their kids grow up different from them and the place becomes different as it absorbs them. Govanhill is so densely packed that you can see myriad examples of both kinds of parenting walking down two or three blocks. So, you’re going to be Scottish, but Scotland will also be a little bit you.

But what can I give you of the United States, of your heritage? It’s a tricky question because of American culture’s absolute dominance here and its role in holding together the geopolitical order of capital. It’s easy to scoff at the very idea of “American culture” when you’re intoning it to people whose own culture is comprised of the Simpsons and McDonalds, where British children call Father Christmas Santa Claus just like children in rural Ohio, where “America” is not so much a place as a brand concept. Maybe you’d be better off if I gave you less of the United States rather than more.

When you were tiny, Sal, I found myself singing old American folk songs to you. I didn’t quite know why then, but I do now. It’s because there’s something in there, something I know about, that you can’t get from the merchandise that passes for American culture. And it’s not something cryptically American—this folk music is certainly of a place and a time, but it’s lasted as long as it has because it applies across places and across times. And that’s something that the best American culture is good at: capturing a small kernel of the most ordinary human experience and elevating it to the status of a story.

I’m always talking about jazz because jazz tells the story of a very specific idea of the United States—but ideas, like art forms, grow out of the real, concrete, living world, not just out of people’s brains. So telling the story of jazz is a way of telling the story of how the country got the way it did and came to think of itself the way it did because jazz was the first truly American art form.

But folk music is different—first of all, a lot of these songs aren’t just old, old tunes handed down from person to person across the US in a natural way. The reason I can play them for you in recorded format is because some specific musicians and archivists (like Pete Seeger for example) set out to create a recognisably American popular culture that would bring people in the country together and foster a sense of solidarity. It was a deliberate attempt to project an image of the country to itself in a way that pushed back against powerful people doing the same thing for their own selfish ends.

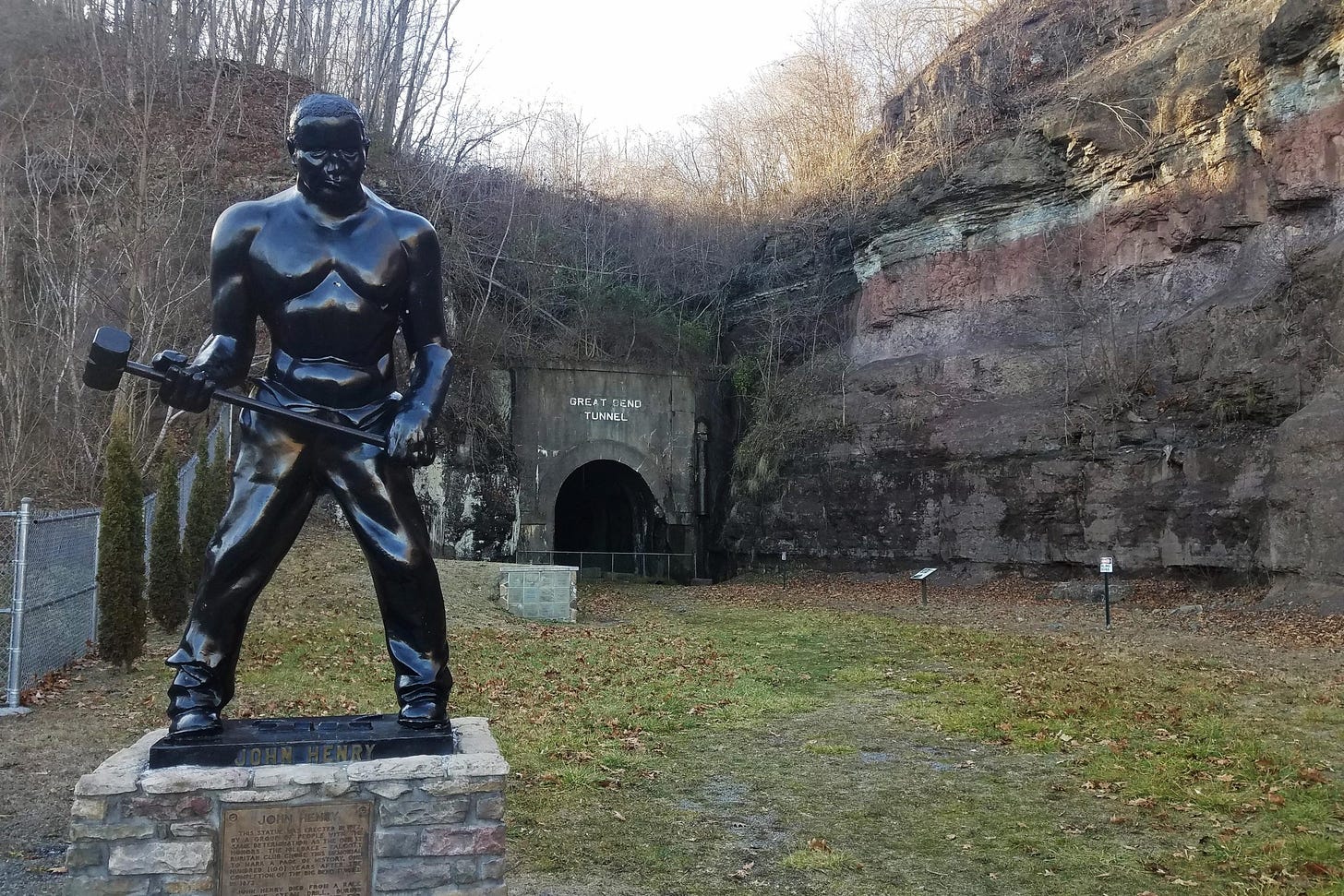

I’m going to play you some records now. The first is Pete Seeger singing “John Henry”, an old folk song that’s been sung with different verses, a different plot, a different melody, a different rhythm—but I like this one the best. Pete Seeger was really famous by the time this was recorded in 1980, so everyone who came to listen also came to sing along. In the folk tradition, the song is structured in a way that makes it easy for the singer to get people to sing along, which Pete Seeger explains at the beginning. It tells the story of a father who works at a job where the bosses are trying to replace human workers with machines. It ends with the dad dying and the son understanding who his dad was and why he did what he did.

It sounds tragic when I put it like that, and it is tragic that the character of the song has to die; it’s a tragedy in the sense that good people are destroyed by forces to which they are morally superior. But the song resolves with the singer telling us that John Henry is still around despite being dead. The problem of bosses trying to replace us with machines is also still around, so it’s a helpful reminder that people can outlive the bad things other people do to them, even when they seem to be dead—and that there are ways of living that are worse than dying.

I really wanted to show you this song because it gets to the heart of something important—you are who are because of your subjectivity, the world behind your eyes that no one knows but you. No one else is like you exactly. You’re Sal, a person seeing the world through your own eyes and everything you see and feel and experience will be filtered in a unique way through that set of conditions that make you you. But you’re also incomplete—you need other people. All of your needs are outside of yourself: food, shelter, the tools to obtain these things, help using those tools, language to map out the world and people to speak it with, love, sympathy, understanding—these things are basically like limbs or organs but on the outside of your body and they’re all bound up with other people. And so you are, in a very real way, who you are to other people.

The problem here is that those external limbs and organs you need to survive and to be happy and to be Sal are subject to this crazy thing called ownership—they are this weird, distorted thing called property. That means that some asshole you’ve never met and will never meet has decided that he owns them and that since you need them to survive, you’ve got to work for this asshole to get money to pay for these things. And because the whole of society is structured like this, everybody is in the same boat: we’ve all got to become this one way to do the job of getting the money to buy the limbs and organs that even though they’re part of our body are not attached because we need them to survive.

And another problem is that this way you’ve got to be in order to do the job to get the money to buy the limbs and organs from this asshole who shouldn’t have them in first place—it’s antithetical to your nature. Even though you are who you are to other people, the thing that makes people great is that they’re all different—too much of the same thing means you’re made up of all the same stuff, like soup made entirely from water. And what’s worse is—it hurts. It hurts a lot to force yourself to be this thing that you’re not.

So John Henry said to his captain, “A man ain’t nothin’ but a man, but before I’d let your steam drill beat me down, I’d die with a hammer in my hand” because it’s better to die fighting than it is to be crushed to death in the act of contorting yourself into the shape that some asshole and his machines insist you should be.

You might not quite realise how much this fight has shaped everyday life for you and every person you know, because people themselves don’t see it that way—we’re all too busy trying to keep those limbs and organs attached. It takes up all of your mental bandwidth. But believe me, kiddo, it’s the defining impulse of our society. Take it from your old dad.

And there have always been people who fought rather than submit—fought for this thing called democracy. Being half American and the other half Scottish, you’re bound to hear this word being bandied about, especially in the mouths of the people who have nothing but contempt for it. When they say it, they mean it in the narrowest sense—ticking a box every four years or so. That’s not democracy. There being a vote in a building in London that you’re not even allowed into isn’t democracy. Even if there is democracy in there, that’s not democracy in the true sense. It’s only democracy if it’s everywhere that people are: the home, the workplace, the public spaces, the schools and institutions.

If you’re unlucky enough to work a job, which I’m fairly sure you will, you’ll immediately be faced with the lack of democracy that I’m talking about: the boss tells you what to do and who to be and you do it and be it or they take away your ability to survive in the world. It’s a dictatorship, though most people don’t really call it that. But don’t worry, Sal—you’re in good company. People have been fighting for a democratic society for as long as there has been a society.

That’s what the next two songs are about: first, Billy Bragg and Dick Gaughan singing “The Red Flag”. Now, this song normally gets sung to the tune of “O Tannenbaum”, a German Christmas carol—a slow, depressing dirge—but the guy who wrote the lyric set it to a fife and drum melody called “The White Cockade” that the drummers and pipers of the Continental Army played on the battlefields of the American Revolution. The author of the song, James Connell, wanted to rouse people who heard it to fight energetically for a world where no one person was subject to the power of another—what I’m talking about when I use the word “democracy.” Though Connell probably rolls in his grave when Kier Starmer sings it at the beginning of the Labour Party conference every year.

But you and I both know what this song means—you’ve bounced on my shoulders ecstatically so many times while we danced and sang this one together. It’s about the world that I want for you.

After that, we’re going to hear “Hallelujah, I’m a Bum” by Harry McClintock, who performed under the name Haywire Mac, the singing hobo. A hobo was a person who hated work so much that he’d rather walk across the United States looking for a handout or sneak onto big freight trains. Hobos would go to great lengths to not work, which nowadays is the kind of thing that people despise. You’re supposed to want to work, which is just stupid. Don’t get me wrong, if you love what you do then you will want to work—I love doing this show and I spend a lot of hours at it (mostly while you’re sleeping). And if I could make a living doing this, I would work even harder at it because I wouldn’t have to waste a lot of time and energy tending the machines and destroying myself for the benefit of some asshole.

But sometimes you can actually avoid being destroyed, usually by sacrificing a certain degree of comfort or by banding together with others and fighting back. This song was an anthem for those kinds of people. It was the marching song for a group called the IWW, the Industrial Workers of the World, who did a pretty good job of fighting the dictatorship of work. They lost in the end, but they did a lot to claw back some of those limbs and organs. So, as old Haywire Mac says, “Rejoice and be glad.”

As I’m writing this, you’re asleep in the buggy at my side. It took me hours to get you to nap, walking up and down Victoria Road trying to avoid the blazing winter sun shining in your eyes, making sure you’re not too cold, comforting you when you cry for your mom, for a toy digger, for a thing you can’t articulate and that I can’t figure out…

You know, Sal, I sometimes look at you sleeping there and feel the tremendous responsibility I have to you as my son. I know you very well and I know your needs, but this feeling of responsibility also reminds me that I was failed—and having been failed, I don’t really know what success looks like. Before you were even born, when I heard you were going to be a boy, I had a little moment of terror: a searing shaft of ruthless light shone on a darkly hidden fear that the long line of bad or absent fathers, in which I’m the latest, was somehow biologically determined.

The next record I’m going to play is an old Greek song in the rebetika style: “In the Cool Morning”. It’s one of the genre’s most famous players, Vassilis Tsitsanis, singing about being a mangas—a playboy who flouts social conventions and smokes hash all day. Rebetika is the Greek equivalent of the blues or jazz because it’s the only truly Greek music form, though the people who originally played it were ethnic Greeks from other countries and the character of the music is as Middle Eastern as it is European. Like the US’s relationship to African American culture, the Greeks had a hard time accepting this “foreign”-sounding music—until, of course, it went from a folk music to a popular music to the much-lauded national art music of the country.

Your Papou, my biological father, was born in a tiny village on an island in Greece. His father wasn’t a good parent to him, wasn’t even really around that much from what I’ve been told. I wouldn’t necessarily describe either of these men as manges, but the image of the carefree man who keeps himself unencumbered by responsibilities is a potent one that spans cultures, music genres, even centuries. The man who’s free from responsibilities, or who fulfils them effortlessly, is more of an archetypal, aspirational figure than a real-life one and you can see it drawing men away from their families like a siren call. Following that call, these men end up drowning in their own selfishness because I certainly have never met a single one who was happy or free, though I’ve seen enough of them old and lonely.

To be totally honest, it’s not difficult to understand the impulse to bolt when the going gets tough, because the going really is tough for a parent: the seemingly endless nights of interrupted or non-existent sleep when the baby cries and cries like a trapped animal; walking around the same square mile at a snail’s pace all day looking for something to do or waiting for the kid to nap; scrambling frantically to keep a toddler from walking into moving traffic or eating bleach or trying to ride a Staffy or throwing themselves into the duck pond; standing shamefaced on the pavement stubbornly refusing to acknowledge the staring passersby when that toddler has a fifteen minute tantrum because you so cruelly prevented them from committing these many and varied suicides.

None of this is your fault of course, and I would never leave you because of it. And it makes you realise that all these guys through the years who’ve thought of themselves as really manly men were obviously just not able to endure it. Sure, it’s probably easier to go with the social flow and slip on the invisibility cloak of gender that absolves you of parental responsibility so you can sit around smoking hash and playing the bouzouki—not everyone is cut out to be a dad.

But before you go thinking that all dads are deadbeats or that I’m trying to claim I’m some kind of hero for braving boredom, anxiety and embarrassment, let me assure you that plenty of men have been good dads. The next two songs, “Coorie Doon” by the Glaswegian Matt McGinn, and “Prayer of a Miner’s Child” by the Appalachian banjo player Dock Boggs, express to me the real tenderness at the heart of being strong. Even the old-fashioned kind of dad wasn’t just some brutal troglodyte who brought home nothing but money to pay the bills and an iron discipline. Men get a bad rap that’s only partially deserved. Lots of men, like any person who has to contort themselves into the shape of a working machine, were only able to endure it because they sat there crouched in the dark, in the dust, in the damp, dreaming about their little ones at home sleeping soundly. Even the most pitiful son of a bitch can get through whatever the world throws at him if he knows that someone loves him and that he’s got someone to love.

Your mom and I talk sometimes about the things we want for you, as well as the things we fear for you, and it isn’t anything specific. When you were tiny, we used to listen to the song “My Blue Heaven” and it sounded almost haunted to us—the quaint idyll that Gene Austin’s recording paints a picture of seems kind of corny, yeah, but also just so... familiar. Once you were able to distinguish between night and day, between yourself and the world, it took hours of breastfeeding to get you to sleep every night. I would write in my journal in the next room while your mother patiently waited for your body to relax and release from hers. I’d reflect while I listened to this song on what I could give you, poor as I am, and what I really wanted for you. After months of thinking about it, a couple of years at this point, I think the most important thing I can try to instil in you is the ability to know and love other people unreservedly.

Love for others has given humans the ability to face firing squads, to ascend the gallows without hesitation, to give up long lives to a cause not in a fit of passion but patiently and enduringly, to sacrifice comfort and reward and recognition—because they felt love and knew in their hearts that they were loved. The willingness to know others deeply and to be known is a prerequisite for self-understanding and it’s the foundation of love between people. It’s also terrifying. It requires a huge degree of vulnerability; it is, without exaggeration, revolutionary in its potential, and without this love, nothing of worth is possible or even desirable. But it hurts sometimes and it’s embarrassing and it’s also impossible to be this vulnerable while also maintaining the illusion that you’re something special, even especially pitiable. So the measure of our success as parents will be the extent to which you can love and allow yourself to be loved.

You’ve taught me this, Sal. We stumbled into parenthood without knowing what it would be like, hoping to build “a little nest that’s nestled where the roses bloom,” just like so many other people—but it was too hard. So we ended up meeting other parents with kids of a similar age walking around Govanhill aimlessly, haunting the parks and preventing their toddlers from drowning in a duck pond. After a while, the parents from other places—the ones crowded together in little flats, with no family around, no childcare, not enough money—all recognised each other and slowly came together as a kind of unit.

This is your group of friends, kiddo. This is your working family, who you see every day and who look after you and you look after. Govanhill gave us that—the setting for creating family out of nothing, for filling in the gaps where civil society should be. And you gave us the impulse—you pushed us outside, out into the world, into the arms of other people, where we would have to learn to love others for the sake of our very survival. It’s probably the best thing that’s ever happened to me.

The Christmas myth, the nativity and all that, seems like a good and relevant one to me. Mary and Joseph were escaping the terror of King Herod, who declared that all newborns be killed to prevent the birth of a prophesied Messiah. I’m sure that at least one of their modern-day counterparts in Gaza is giving birth right now, maybe not in a manger, maybe with no kings coming to offer gifts. One day I expect you’ll ask me about this time we’re living through, to account for myself in the face of something so awful, but what can I tell you? We only do what we can do. I have no idea, no frame of reference for understanding how a person endures that. But I suspect when they see their little baby for the first time, they’ll see something more than just a child. They’ll see the promise of a future, a whole cosmology of life triumphing over death, life itself and all the love in the world.

Merry Christmas, Sal. I love you.