Beside the Golden Door

A Love Letter to Govanhill

Listen to this article here.

Since I left my childhood home in the great State of New York, I’ve moved house thirty-three times.

That’s a lot, but I’m not special. It’s a common story now: people can’t afford to stay put because rents go up and wages stay the same.

When I moved to Glasgow, I sincerely hoped—beyond both hope and reason—that I’d left my moving days behind me. It’s kind of tough, feeling like the only home you’ve got is the travel-sized piece you took with you. My partner and I eventually found a flat in Shawlands, settled in and made plans the way you would if you fully expected not to move again for the foreseeable future. It was foolish, in retrospect.

After three and a half years in that flat, the landlord sent us an official notice of rent increase: a 21% rise. We pleaded with him, reasoned with him, implored him, even argued. ‘I can’t be expected to stand still while the market moves on,’ he wrote. The anonymous brains at the first-tier tribunal tasked with protecting tenants evidently agreed. Not only did we have to move out, but the landlord also connived to keep our deposit.

Because this all happened in the midst of a housing crisis, it looked for a minute there like we might actually have nowhere to go. It wouldn’t be the first time in my life. But it’s hard to surf couches when you’re already hauling one around.

Lucky for us, some friends were leaving their flat in Govanhill, where we’ve worked and hung out for years, so we took it over. Now, here we are. Maybe thirty-third time’s a charm.

The Scotsman ran an article in 2013 with the headline: ‘Govanhill: Glasgow’s Ellis Island’. Having come to Govanhill myself via the hereditary route of New York’s Ellis Island, the title struck me as a canny dodge of some pretty tricky conversations about both the US and Scotland.

The casual conflation of ‘Ellis Island’ with ‘Govanhill as a historically welcome place in Scotland for migrants’ sounds like so many outdated talking points from the world of almost ten years ago, before Kids In Cages or one-way flights to Rwanda. Historical amnesiacs often forget—or ignore—that, judging the US’s track record on race and class, we should absolutely be aiming higher. And like the parts of New York most fetishised for their “diversity” (shout out to Brooklyn), Govanhill’s reputation could go from neglect to Negronis in a dizzyingly short space of time.

But since we’re talking about a little Lifestyle feature in a right-leaning rag, maybe I’m being too critically demanding. The article was, after all, as much about food as it was about migration. Or is it the other way around? Though nestled in the ‘Food and Drink’ section, the author conjures the gritty realities of racism, crime, poverty and the bloody history of populations in transit. He seems to be talking obliquely about something else, whatever it is—or perhaps he’s avoiding that something else altogether—by talking instead about the neighbourhood’s rich culinary culture.

‘The story of Govanhill, its people and its long history of immigration is best told by talking to those who prepare and enjoy its food and drink,’ the author says before doing precisely that. And after relating the wide-ranging views of these preparers and enjoyers, the article ends: ‘Govanhill is great for food, no doubt. It’s also a fine place to feed the soul.’

It’s hard to imagine anyone publishing an unreconstructed love letter to an under-served majority-minority neighbourhood like this in late 2022. Why? Not because Govanhill doesn’t deserve it, or that people don’t actually feel this way about the place; but because as rents and house prices skyrocket, so too do the stakes for its residents. The author’s romantic cheeriness signals that he enjoyed visiting Govanhill—which implies that he doesn’t live here. This kind of flâneur journalism, praising the exotic beauty of the city’s larder from arm’s length, reads today like the threat of property developers pricing us out of it.

If you’re going to write about a place, as I am currently trying to do, where over a century of cultural fermentation may well be sterilised by a few dozen landlords in a handful of years, it’s worth remembering that living communities must be the subject, as well as the object, of history. I guess in practice this means understanding how a place feeds itself and allowing your soul to go on a diet.

But the journalist who touted ‘Glasgow’s Ellis Island’ was invoking the zeitgeist. Migration and food both still play an outsized role in the way people view Govanhill, and they’ve certainly influenced the course of its development since the mid-nineteenth century.

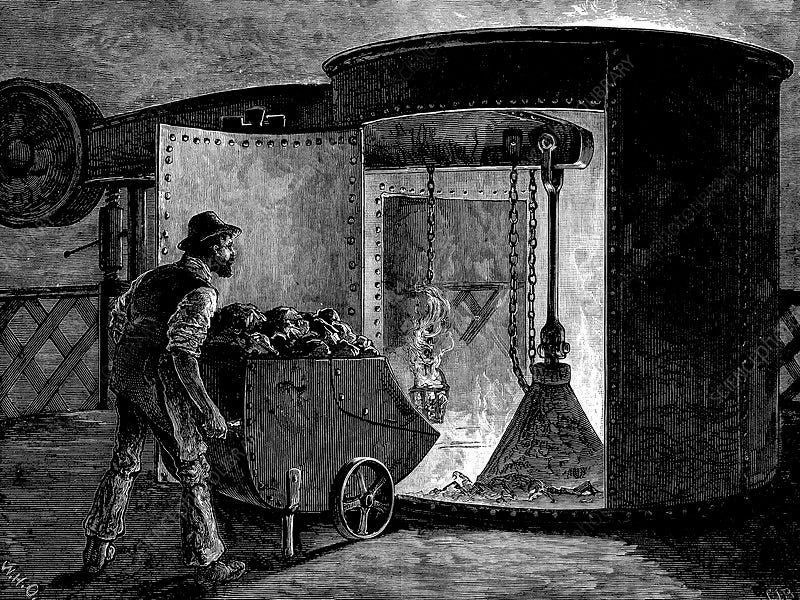

Govanhill was founded as a company village for workers at the now long-gone collieries and coal-bearing wagon paths extending from Allison Street all the way to the River Clyde. The coal mines provided fuel for the iron foundries a mile up Cathcart Road at the Govan Iron Works—or ‘Dixon’s Blazes’, as it was known by the workers producing iron and steel, so named for the family who owned the entire area.

Many of the workers who came to Govanhill in the middle of the nineteenth century were Highlanders facing ‘clearance’ in their home towns and villages. Local lairds uprooted and even destroyed rural villages, driving tenant farmers off the land (or ‘clearing’ it) to make way for more profitable sheep grazing. This forced the dispossessed workers to seek new lives in the slums of industrial centres like Glasgow, by then boasting the worst and most overcrowded living conditions in Europe.

Many others were Irish migrants escaping the famine of 1848, when Irish potato crops suffered a blight that could have left enough for the sharecroppers to eat, but not enough to provide the landlords a surplus. The landlords, of course, took what was left of the crop and allowed the sharecroppers to starve, even setting fire to their houses and driving them off the land when they failed to make payment. Ireland’s population dropped from eight million to just over four million (a drop from which it has yet to recover), with millions dying and many emigrating to the United States—or places like Govanhill.

By the late 1870s, the village had grown into a town. In 1891, it was incorporated into the City of Glasgow. The tenements for which the neighbourhood is known were built between this time and the 1910s. These tenements housed an increasing number of skilled and semi-skilled workers from the Highlands, from Ireland, and from the 1920s it received a wave of migrants from Italy and Jews from Eastern Europe. Victoria Road swelled with shops and amusements for those with disposable incomes, often operated by these new arrivals who brought with them espresso, gelato, fried fish and potatoes and other now-familiar fare.

From the 1950s, Glasgow Corporation undertook a policy of slum clearance and urban overspill, razing old tenements to the ground and separating generations-old communities out into isolated housing schemes on the outskirts of the city. There were few jobs, shops or amusements, if any, and transport back to the city was infrequent, expensive and time-consuming. Govanhill managed to avoid this disaster of bureaucratic city planning. Residents later formed a housing association that took administrative control of the social housing in the area and used compulsory purchase orders to seize derelict buildings from rogue landlords.

In the 1960s, Govanhill became home to many Pakistani people arriving in Britain, with Allison Street still serving as a strip of Asian groceries, restaurants and takeaways. Cathcart Road to the east is home to several tailors and clothing outlets catering to the Pakistani community. In the last twenty years, the neighbourhood welcomed migrants from Eastern Europe, including Glasgow’s highest concentration of Romani people. Again, the number of Romanian groceries along Allison Street and the side streets adjacent, as well as the copious shells of sunflower seeds peppering the pavement, stand as a testament to the settlement of this community in Govanhill.

With wages across Britain (and the rest of the West) stagnating since the early 1980s, while the cost of housing, food and energy has risen even above the level of inflation, domestic migration within Britain also changed the demographic composition of Govanhill. Where Glasgow’s West End once housed people on low incomes, students and artists, the gentrification of those neighbourhoods and their rising rents pushed people south to areas like Shawlands, Mount Florida, Cathcart and Govanhill. Edinburgh also witnessed the highest rent increases in Scotland over the last ten years, with average rents peaking well above £1,000 per month long before Glasgow recently crossed that milestone. With rents nationwide shooting up by over 33% in the last decade, people from across Scotland come to the Southside because of its relative affordability, while visitors come to eat and drink.

Glasgow is an attractive prospect for young people in other parts of Britain who can’t afford to stay where they are: cities like London, Bristol and Manchester, where the gap between the rate of pay and the cost of living continues to grow into a yawning chasm. And in Ireland, where rents in cities like Dublin are amongst the highest of anywhere in Europe, young people have viewed Glasgow as a good option for living in a reasonably sized English-speaking city, with opportunities for a decent work-life balance.

But the downward pressure on living standards in the rest of the UK and Ireland are taking their toll on Glasgow too, and especially on already under-served areas like Govanhill. So with this influx of (mostly) young and often downwardly mobile people who can’t afford to buy their own homes or stay in the towns and cities they come from, the businesses that cater to them—cafés, brunch restaurants, bars and groceries—soon followed.

Some people call this process ‘gentrification’, and sometimes they’re correct—though we need to be clear and distinguish between a neighbourhood simply changing (which is inevitable) from a neighbourhood being gentrified (which is not). People move into a neighbourhood from other places, often out of pure necessity, and the neighbourhood accommodates them without displacing anyone. A variety of communities have settled in Govanhill over decades and the area is now home to all of them. The migratory patchwork gives Govanhill its distinctive character.

Gentrification, on the other hand, is the process by which property developers, lettings and estate agents, landlords and investors transform poor and working class neighbourhoods into uniformly bourgeois sites of upmarket businesses and “desirable” properties by displacing the often well-established and close knit groups of people who live there.

You don’t have to destroy a community to make their neighbourhood nicer; indeed, not everything that’s expensive is good. But the agents of gentrification are parasitical: poor and working class neighbourhoods are profitable because they are cheap and can be made expensive. Clearing unwanted people out of these areas earmarked for “development” is a key step in the process: you can’t gentrify a desolated industrial district where no one lives because no one actually wants to live there.

In fact, even not-for-profit public development projects aimed at under-served neighbourhoods can be grist to the gentrifiers’ mill. Take Govanhill Baths on Calder Street for example: the building sat derelict for decades before a dedicated and quite radical local campaign fought and won action from the council. The Govanhill Baths, now under reconstruction and opening to the public soon, will unquestionably benefit the residents of Govanhill—that is, if they can still afford to live here when the baths built for them likely increase the property value in the area.

It would be absurd to describe The Govanhill Baths Community Trust as gentrifiers, as it would be to describe the plucky fight for a public pool in an under-served community as gentrification. But even these laudable community victories can be exploited by landlords and property developers as public subsidies that raise the value of their investment and ultimately cater only to the rich, a kind of fattening for the slaughter.

Govanhill is undoubtedly being subjected to gentrification. The Scottish Government’s announcement of a rent freeze and eviction moratorium up to March 2023 notwithstanding, rents in the area have risen over 15% in a year while evictions spiked. Looking at the longer term, rents in Glasgow have soared by nearly 64% in the last decade. Meanwhile, Scotland’s child poverty rate is at its highest here in the heart of the First Minister’s constituency, at a shocking 69%—nearly three times the national average.

Unaffordable accommodation is a big part of that. The average rent for a two-bed flat in the G42 postcode is now over eight hundred pounds a month: a person splitting this rent with a partner or flatmate would need to be taking home at least £19,200 a year after tax and deductions to keep their rent at a safe quarter of their earnings. That’s more than I earn as a Band 3 NHS worker.

With property prices spiralling, many flats and houses in Govanhill have moved out of owner-occupation to join the buy-to-let profit bonanza, making home ownership impossible for many people who only a few years ago would have been able to buy. Every tenement flat that enters the private rental market puts upward pressure on rents and house prices, as landlords consolidate their grip on already limited housing.

Meanwhile the Scottish Government fails to build more social housing, with existing stock privatised and allocated to the property management corporation The Wheatly Group (through their subsidiary, Glasgow Housing Association). But even this dwindling number of social tenants are now facing rising rents to ensure that Wheatley turns an ever-higher profit. This lack of downward pressure on prices combined with ever more tenants having no option but the private rental sector is pushing up rents on remaining properties to completely unaffordable levels for people in Govanhill.

Since establishment media talks about this infrequently and in limited terms, it’s unsurprising that people will instead blame migrant residents themselves for the poor condition of the neighbourhood, while in the same breath point to new shops in the area as harbingers of gentrification, often attributing the rising cost of housing to these businesses. A certain reactionary strain of anti-gentrification sentiment will also blame the people they think shop and work there—the old “avocado on toast” straw man.

Take Locavore on Victoria Road as an example. With their faux-leftist branding—an upraised fist full of leaves under the words ‘TAKE CHARD’—Locavore is one of many ‘community interest’ operations hocking expensive organic food and a narrative about themselves as an alternative to capitalism, while at the same time…you know, just basically doing capitalism.

Locavore employs mostly young university graduates who in any previous period since the Second World War would have found jobs that didn’t involve sweeping, mopping and stacking shelves. While this cohort is obviously “privileged” compared to the people here facing serious deprivation, that argument totally ignores the true balance of power—and is unsurprisingly broadcast loudest from the last upwardly mobile generation, who are themselves more likely to be landlords.

Blaming young people for gentrification falsely assumes that they’re in these jobs, and even in this city, because they simply chose not to stay where they were. Really though, dramatic changes within the economy over decades have sent millions of people across the country and even across continents in search of a place like Govanhill: somewhere to live, somewhere to work, somewhere to have a social life and a family.

It’s debatable whether a company like Locavore is a symptom or an agent of gentrification. In one respect, they attract (and rely on) consumers who are able (or at least willing) to shell out on premium groceries, and this is unlikely to be Govanhill’s current demographic majority. On the other hand, they’re not a private equity firm with thousands of rental units in their portfolio: they rent like the rest of us. If Locavore does indeed drive up property prices, then eventually they’ll gentrify themselves out of a piece of prime real estate.

Govanhill’s problem is not the number of brunch spots in one square block, but the class cleansing of urban areas happening across wealthy western countries. If you can afford your groceries, you probably don’t care what the yuppies are up to. The Govanhill Baths Community Trust seem to understand the stakes here, opening the People’s Pantry in 2020, where membership is a few pounds a week and gets you a basket of groceries worth the cost of a single Locavore chicken. Of course, the waiting list to join is currently around one year.

But the question of whether shops like Locavore contribute to gentrification (or whether charities like the People’s Pantry can alleviate it) misses the point, I think. It ignores the everyday volatility of life under capitalism for people who are not its subjects but its objects. The market’s shifting winds that set people in motion to and from places like Govanhill also wear away the living standards of long-time residents and recent arrivals alike, which has led to the current upsurge in industrial actions. Workers from the railway, the post office, city council workers including the guys picking up the rubbish, and perhaps soon NHS Scotland are all going on strike to fight for pay that actually meets the cost of living. Hell, even Locavore workers are unionising.

At the same time, tenants unions like Living Rent are campaigning and door-knocking to build tenant power street by street. There’s no doubt that had Living Rent and others not piled pressure on the Scottish Government to take action on tenant protections since 2014, the recent rent freeze and eviction moratorium would have been unthinkable. And it’s no coincidence that at every picket, from the cleansing workers at Polmadie Recycling Centre to the posties at the depot on Victoria Road, you’ll see Living Rent members flying the green banner in solidarity with the strikes. Being crushed by soaring rents is substantially the same problem as being crushed by low pay.

Tenants and workers, old townies and blow-ins, employed in a traditional blue collar industry or flogging organic vegetables—or not employed at all—the thing we have in common is the drive to live well and not alone, balanced against the rising cost of food, fuel and shelter. Some move on, many more arrive. And as we make the place ours, calling dibs in whatever language, dressing our nests and stoking our fires, investors and developers speculate on the very qualities that make this neighbourhood home.

While the SNP and the Scottish Greens make mealy-mouthed promises of rent controls in 2025, landlords prepare by jacking up rents. If the current rent freeze ends in March next year as planned, before these rent controls are due to take effect, the baying dogs of private property will pounce. It’s hard to imagine where there is left to go.

As tenants as much as workers, the only way to even stand still is to fight, together.

Standing at the top of Queens Park looking north into the city, over the grid system of tenements and potholes, cycle lanes and broken street lamps, a distant building reads in bold type: PEOPLE MAKE GLASGOW. It’s a funny one, because the phrase is true in a shallow sense, but what do these platitudes really tell us? People also make satellites and rocket ships and morning rolls and Tennents lager and buildings and books and statues and signposts and iPhones and guitars and medicine and freighters and lorries and laser guided missiles and prosthetic limbs and kalashnikovs and Bentleys and chow mein and super yachts and Amazon fulfilment centres.

People make them alright, but do they get to keep them?

The beautiful thing about strikes and struggle is, you know that everyone involved believes they have a future. Why else would they bother? The moment you see someone shrug and say, ‘ah, what difference does it make,’ you know it’s game over.

Govanhill’s future is unwritten. And it could go either way. The architecture of a gentrified neighbourhood stands eerily as a monument to the place it used to be. Time and place: the more you give of the one, the more you belong to the other. And despite its long history, it’s early days for Govanhill.

Every morning when the sun hits my neighbours’ windows and covers my living room in a buttery glow, where my cat sits warming himself while the kettle starts to whistle, the landlord, the prime minister, the king—all furthest from my mind. My partner is pregnant with our first child and I look at the schoolyard out my back window, the sound of the bell and kids arriving screaming and running, parents at the gate waving goodbye. I wonder about my son: what part of Govanhill he’ll want to keep and what part of him belongs to it, how many Romani words he’ll learn and maybe teach me, this person who I haven’t met yet but whose life is so intertwined with mine.